A Trip West

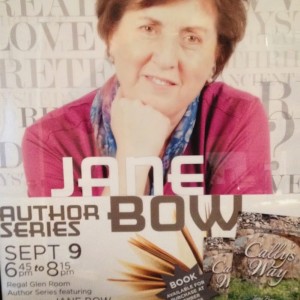

When three invitations to present my new novel, Cally’s Way, arrived from Edmonton, my husband and I packed the trunk of our second-hand Volvo with books and hit the road.

|

Canada today is very different from the country I knew growing up as the daughter of diplomats. Then, we were respected across the world as a thriving democracy and an international peacekeeper.

Last month our prime minister did not attend the U.N.’s summit meeting on climate change. Today’s Canada muzzles its scientists, harasses PEN Canada, which champions freedom of speech, does not even try to meet carbon reduction targets. Toronto, our biggest city, is run by a confessed drug addict.

What happened? How did that Canada become this Canada? Maybe driving across the country would yield some answers.

Days 1 & 2 – Behind the Pines

Fall is touching central Ontario’s sugar maples with red, orange, yellow, gold. Further north, pines that inspired Canada’s Group of Seven painters find purchase among the Canadian Shield’s granite crags and cliffs.

Chi-chi bakeries populate Muskoka Lakes towns where some of the country’s wealthiest families own summer homes, but drive north for a couple of hours and the scene changes.

Motels, gas stations, small businesses along the highway have been abandoned. Those that remain are suffering, their grocery shelves as bare as some I have seen in the third world. But, noticing my walking sticks, a store owner stops mopping the floor to help me.

|

| No gas today. Sorry for the inconvenience. |

Billboards and signs offer clues to what goes on behind the trees:

Fishing and hunting lodges will fly in their clientele

When I was a junior reporter in Thunder Bay, I spent a weekend at one of these wilderness lodges, helping in the kitchen, exploring the river, playing penny card games late into the night. Forty-two years later the smell of frying bacon still takes me back into that wild peace.

You are now entering a First Nations reserve

A few years ago, while working in a Moose Factory school, I visited a Cree fishing camp on the mighty Moose River just south of James Bay. Hidden by brush, the camp was invisible until our canoes landed. We feasted on grilled, freshly caught fish, learned how to make a duck blind and mud decoys, then sat, silently waiting for the sound of wings. Knowing that each of us was one tiny breathing participant in the great dance of Nature. What a gift!

|

Violence against women must stop

Testimony during a murder trial I covered for the Chronicle-Journal in 1972 took me into a wilderness hunting camp near Long Lac. The accused was a slight, shy eighteen-year old boy. Waking in the night, hearing one of the older women crying for help in another tent, he found her struggling under a large, very drunk man — his uncle. He yelled, tried to wrestle the attacker. Could not pull him off. Finally, in desperation, he picked up the closest object, an axe, and buried in his uncle’s head. A court full of white men sent the boy to prison for life. Where, I wonder, is he now?

Impossibly blue Lake Superior, stretching as far as the horizon, is framed by red granite cliffs polished by the rain.

Barrick Mine

Just for a moment, the wall of trees breaks. A building and pond are dwarfed by a pile of gravel as high as a hill.

Further west, more trees — deciduous, cedar, pine — all vying for every square inch of earth remind me of other parts of the world, where people of different races and faiths are battling each other for control of land they call home. When the rain lets up, blackened skeletal trunks appear where recent forest fires destroyed everything. Under them, light new-green growth has already begun.

Highways up here are new and beautiful. Cities we are passing through — Sault Ste. Marie, Thunder Bay, Dryden, Kenora — all have fast food joints and big box stores. Is this where the money up here has gone?

Day 3 – Flatlands

Manitoba’s highway signs, in French as well as English, remind us that Francophone Canada does not live only in Quebec.

Fields here are huge, seas of yellow sunflowers. Rolled up hay bales advance like extra-terrestrial creatures from a humanless horizon. Platoons of silver silos wait for the grain and seed trucks throwing up dust along the side roads.

Welcome to big agro, farms owned by companies. You don’t need to be a farmer to feel the enormity of the change this has brought. Wooden homesteads nestled into little groves of planted trees lie empty now.

Above it all the prairie sky is the most magnificent living canvas I have ever seen.

Everything here is big. Trains so long you never see the last car carry cylindrical black tanker cars, and goods containers piled one on top of the other. A man I meet later in Edmonton, whose company is involved with the oil industry, tells me some of the chemicals being transported are lethal. I thank God the land is flat, the rail lines straight.

(Two weeks later, while writing this, I read that a train, derailed and on fire near a rural Saskatchewan village, is belching toxic smoke. Heaven help the people and flora and fawna there. Heaven help us all.)

Prairie villages and towns each have their own character. How did Mozart get its name? Langeburg’s central park is decorated with a painted Volkswagen. A hand-painted sign at the entrance to Churchbridge, Saskatchewan boasts of the two NHL hockey players it has produced.

|

||

| Langenburg’s park |

Day 4 & The last Crossing

Winding through low, tawny hills, the North Saskatchewan River valley has been an awesome passageway as long as humans have travelled between the Rocky Mountains and Saskatchewan. As we follow it, heading for Alberta, gigantic farming and construction machines and filthy oil tanker trucks rule the road. We are glad when Edmonton’s skyline appears.

The North Saskatchewan River cuts right through Edmonton. We walk along its banks. Readers welcome me and Cally’s Way. By the end of the festivities I am number two on the Journal’s fiction bestseller list, and it is time to head home.

Alberta’s southeastern cattle ranges come alive, thanks to Guy Vanderhaeghe’s historical novels, particularly The Last Crossing. Then, at Wild Horse, we find a lone guard defending Canada’s border.

Highways are under construction all across Canada and the United States. City exit ramps are clogged with cars, pick-up and transport trucks. At the Ambassador Bridge border crossing in Detroit trucks are lined up for more than a kilometer, engines idling.

Driving the last stretch, through acres and acres of new windmills in south-western Ontario, I try to make sense of what we have seen:

- People we met everywhere on our trip were kind, generous-hearted, very different from each other. I feel grateful to live among them.

- More and more stuff, some of it dangerous, is moving across our awesome landscape of lakes and forest, prairies and mountains. This is not healthy. Neither are our politics.

- But how, I wonder, can Canadians struggling through windswept, six-month winters in isolated places, and working dawn to dusk in the growing season, find the strength or the time to relate to the lives of other Canadians thousands of kilometres away? How can an Albertan from Vermilion know what concerns someone trying to make a living in Windsor Ontario?

Canada became a country because the British needed to defend against incursions from the south. We forced the aboriginal peoples onto reserves, forged a federation of provinces and territories, built railways, and have been making it up as we go along ever since.

Today the Canada we cherish — clean air and water, freedom of speech and open debate, consumer choices — needs our protection. So please, wherever you live, get out and vote, but for people and parties that stand for a free, environmentally responsible Canada.

|

| Peterborough City Council plans to build a bridge here. |

Thanks for taking time to read this,

Jane